A brief introduction

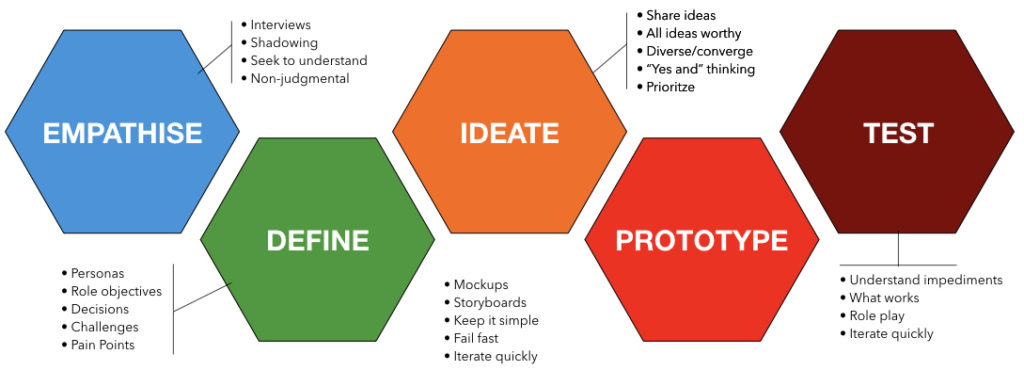

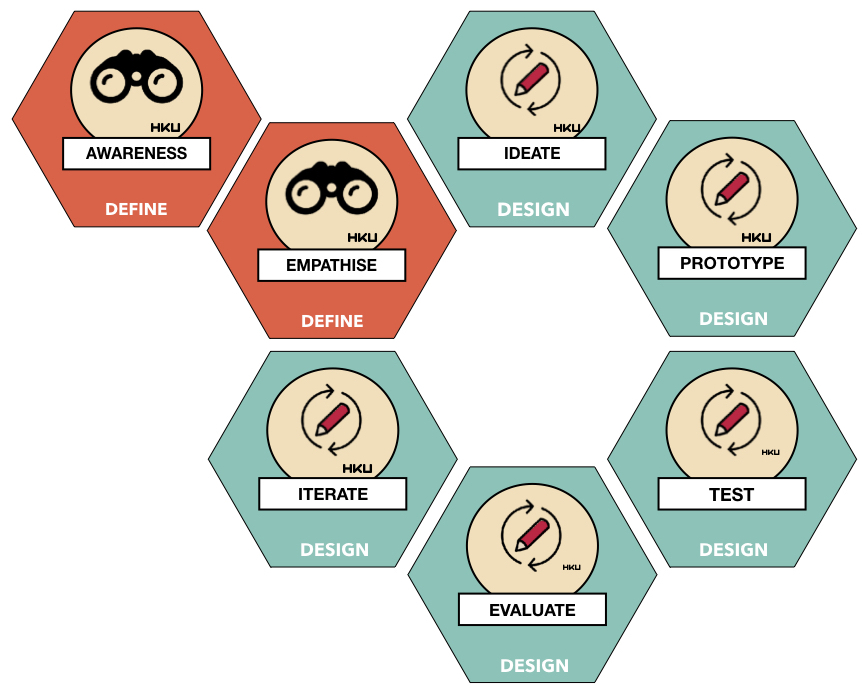

• empathise

The design process starts with a series of activities called Empathise. This means the design team engages actively with their stakeholders or end users and tries to get a deep understanding of their position. Through interviews, or observations (shadowing), and through empathic listening (not judging!) the team learns about the experiences, the emotions, the problems and challenges the stakeholders encounter in the design problem you are tackling.

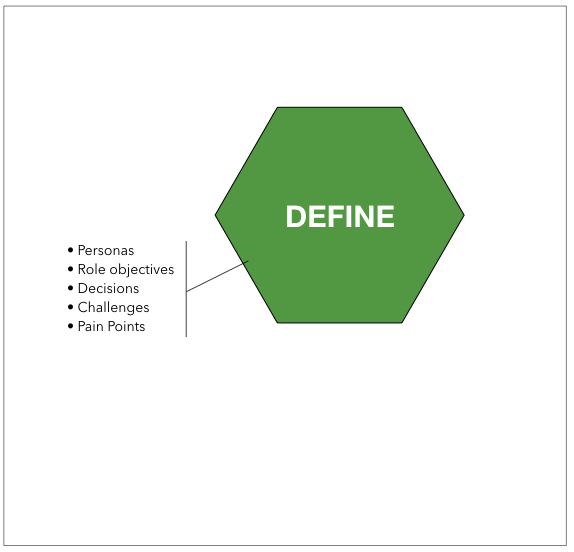

• define

The next step is make sense of all the data, impressions and observations, and reframe the design problem you are addressing. In most cases these data redefine the problem you were starting out with, or the problem your client wants to address. In this phase you will also define the scope of the project, and to identify the key ‘Pain points’ your users experience that your solution needs to address or preferably take away.

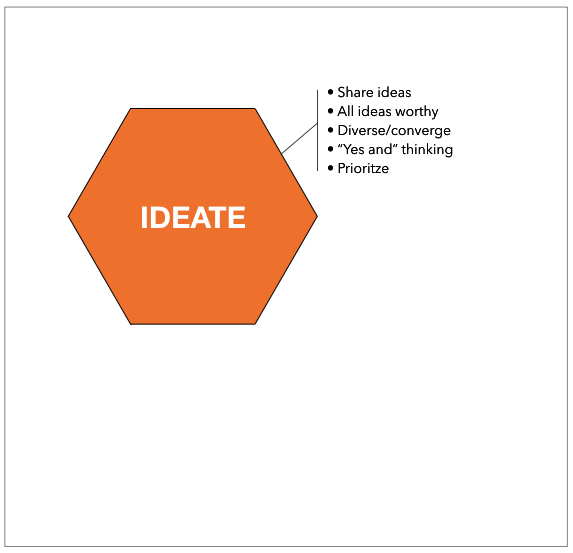

• ideate

In this phase, with the boundaries defined for your project, you will start to use your creativity. Alone or in your team, you will generate and share ideas on a possible solution. In the beginning of this phase, all suggestions are valid; don’t be too judgemental. The process starts with diverting into the subject, exploring many solution paths. After the exploration phase, the team needs to switch gears towards conversion, making choices and finding and deciding on the most effective or possibly most productive solution path.

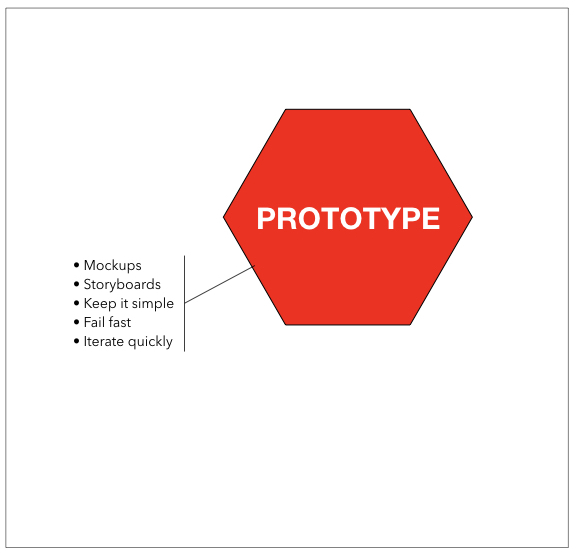

• prototype

A core aspect of design thinking is to start creating the simplest, cheapest, first draft of the solution. These will be rough sketches, storyboards, wire frames, paper prototypes… The function of the prototype is to engage with your end users with these first drafts to learn immediately from your end users whether you stay close to their demands, wishes and needs.

Fail fast means that you do not waste resources on creating a polished solution without verifying the appropriateness of your solution for your stakeholders.

Most starting designers make the mistake of working too long on their first prototype, possibly adding value to an idea that still contains mistakes or assumptions.

An explanation for this is the feeling designers might have that they show something to their end users that is not ‘finished’ or ‘beautiful’ or ‘polished’.

Test

The function of testing is to let your end users be the judge of the quality of your idea. Your users are always right. Initially your concept will probably ‘not work’. Some elements are good, other things are broken.

The most difficult bit in testing is to find our where your design is ‘broken’ and what you need to do to fix it.

You will probably also get feedback that is not relevant to the phase of the design you are in. If people comment on the look and feel of a rough first prototype, those comments should be ‘ignored’. Do not get defensive explaining this to your users. Just receive the feedback and put it aside for now.

For each test you should know up-forehand what it is you want to test. You should do as little explanation as possible. Your design should eventually be able to explain itself. Your most important role is to observe and take notes. If possible and allowed, you might record visuals or audio to reflect later on the test. You might easily miss important cues; body language; individual behaviour; social interactions etc.

Although design thinking has many merits in being used in this fashion, it has some repercussions. The most important downside of this model is the fact it ends with a prototype.

Many innovation trajectories fail after the prototype phase. There are many possible causes for this.

- 1. funding problems; there was money for the prototype but not for production

- 2. implementation; No enough time, training, materials to learn the end users to implement the solution

- 3. the ‘stack’ problem; the new solution is introduced on top of the existing practise; creating work overload. (Golden rule; if you introduce something new, what existing bit/procedure/tool do you take away?)

- 4. Necessary adaptations on the product/service based on real time lessons learned in the implementation

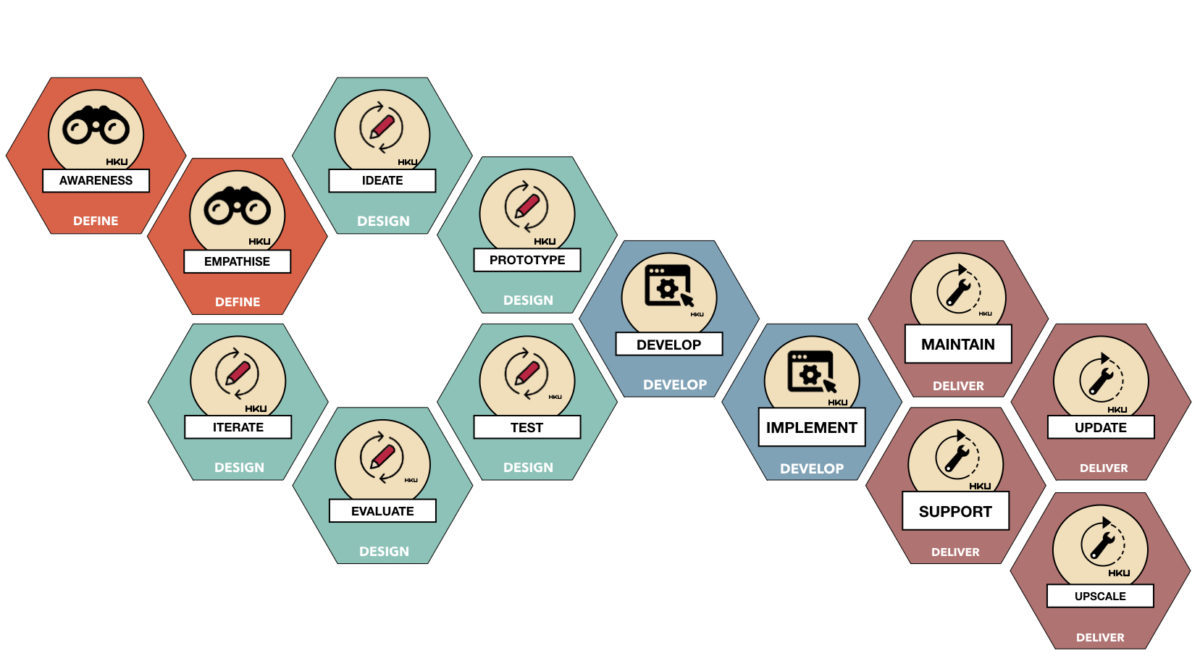

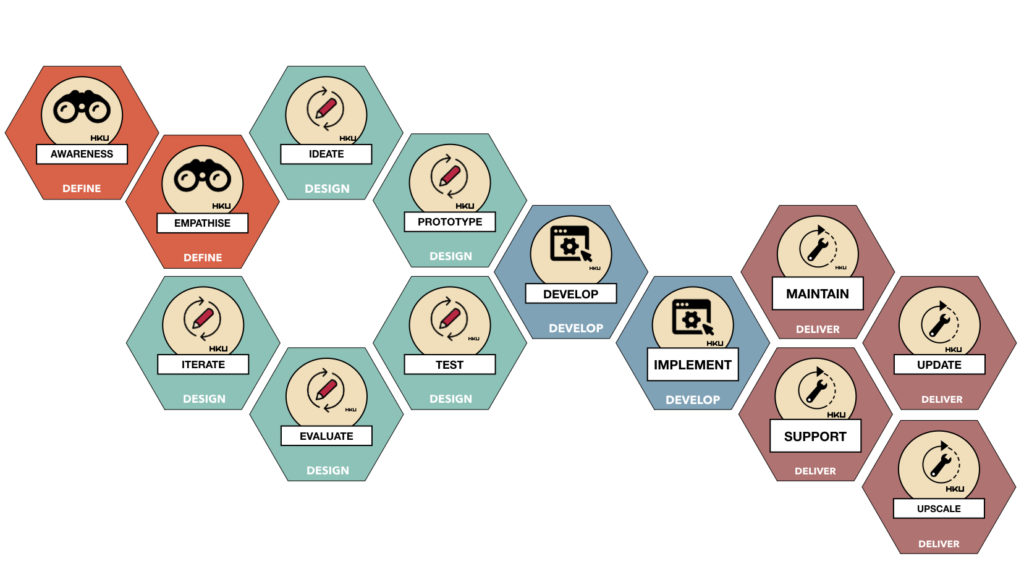

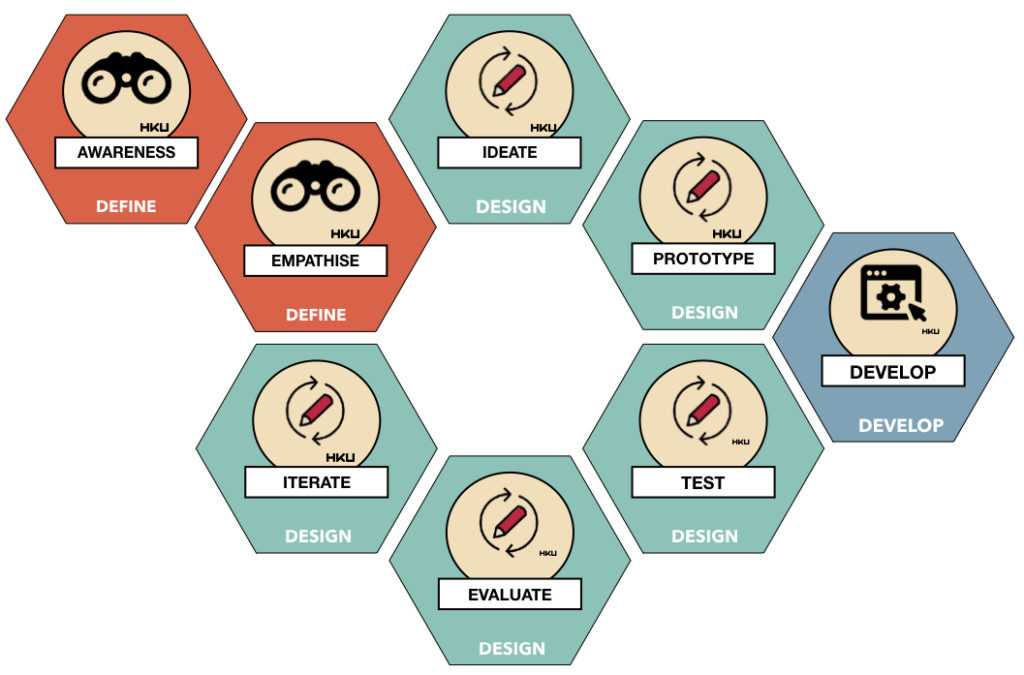

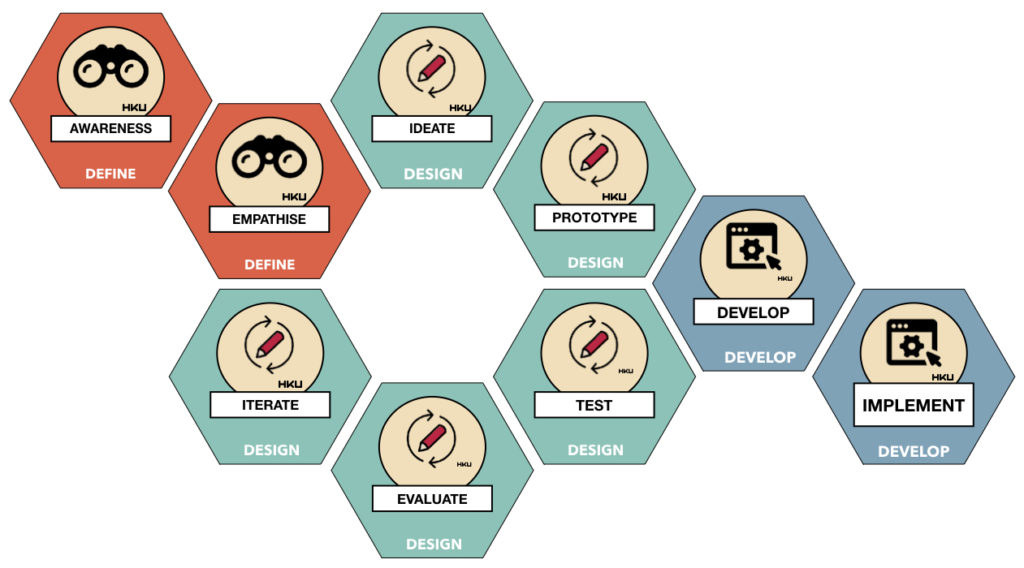

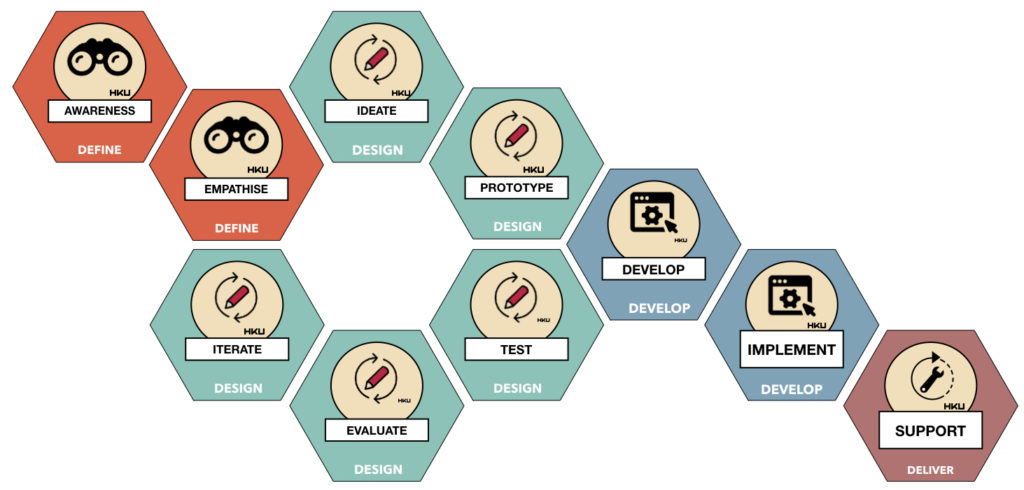

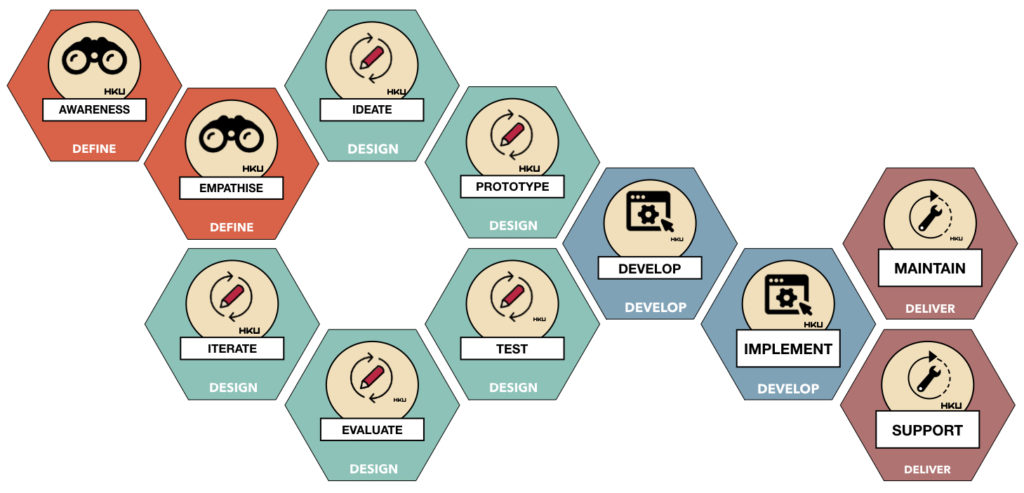

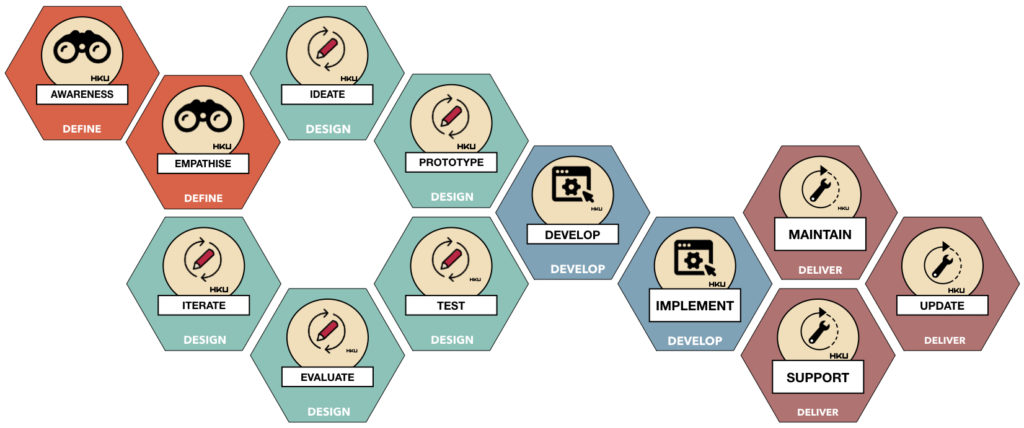

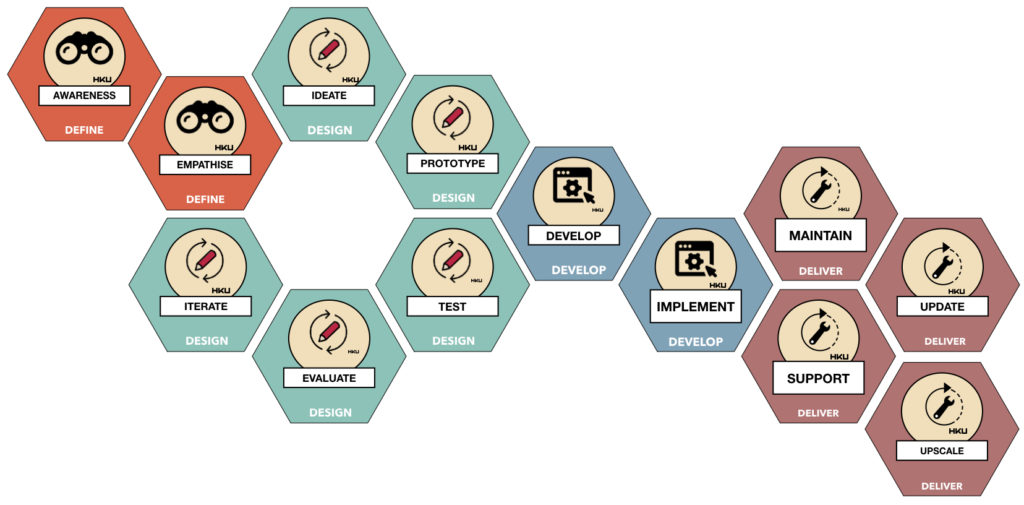

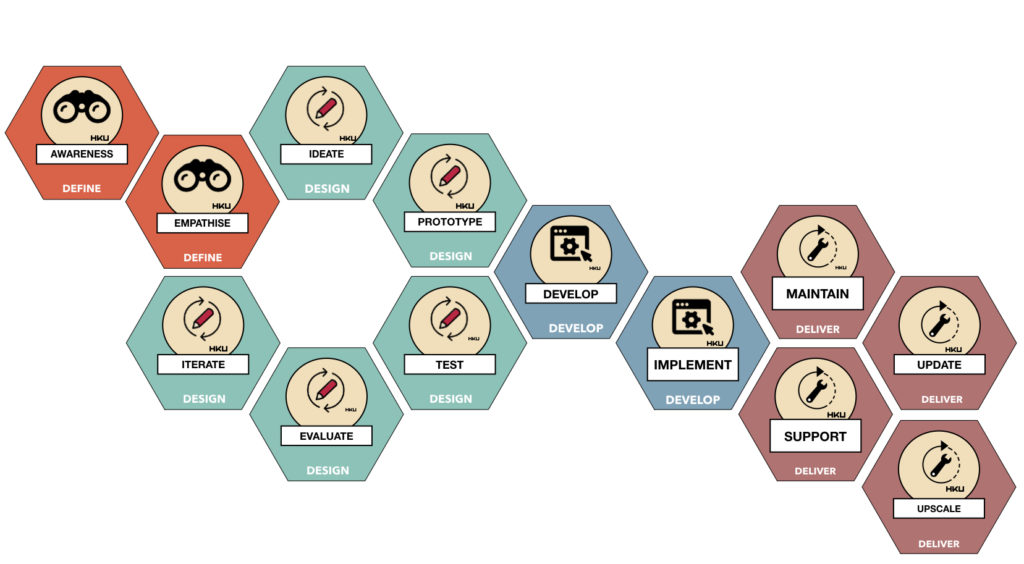

This list can go on and on. Therefore, as HKU we have developed an alternative model, covering the Stanford model but expanding on this.

The model tries to capture the entire trajectory from idea to full usage addressing the main steps.

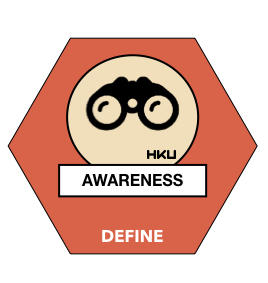

• awareness

If you are doing a project with a client, there is significant chance they will not be as well versed in design thinking as a methodology as you.

Developing a shared language and thorough understanding with your client is really important at the start of a project. This phase is called awareness because it is also the time to ask some ‘difficult’ questions to your client to avoid future problems. Awareness is about looking ahead into the future of the project and identifying critical issues that need to be addressed early on.

Iterative design process

The next phase is a number of steps we already addressed when explaining the Stanford model.

We add a rule of thumb to this model in terms of the number of iterations. For many projects, four iterations (including solid testing) will put you on firm ground to eliminate the most critical break points in your solution. Less is risky, but doing more iterations does not always add value to the insights you can gather through iterations.

More iterations does not always mean better quality. Whenever a test does not yield new major insights, you can assume your design is optimised as best as it can given the resources available…

• develop

The develop phase means turning a prototype into a product or service. If it is a technical product it often means the entry of a new project partner on the scene.

The nature of your project is really important for the next steps of the model. A technical prototype is often not suitable to scale up into development. If it is code based, the code was not build for stability but to explore functionality or design. So technical prototypes should preferably be rebuild to cater for new demands in the final phases; security, stability, scalability, hosting in an organisation and a multitude of other requirements. The costs from prototype to product in these situations is x10 or more!

• implement

Once the development phase is ready and the final product or service is ready to roll, we step into the implementation phase. Assuming you have groups of end users that will work with your solution, these users will have to find a space in their private or professional lives to fit in their work- or life flow.

A common mistake is a lack of time or resources allocated to this phase by an organisation. Often people need proper instruction, training, practise, trial runs to be able to use the solution as intended.

Another pitfall is to limit implementation to the ‘launch’ of the solution.

• support

Successful implementation depends on support. Whether this is a helpdesk, a manual, a supportive website, instruction sessions… users can get lost.

Support is often undervalued in implementation; poor documentation of scaffolding material can ruin an excellent innovation.

• maintain

Modern interventions are seldomly finished. Especially digital products need constant care due to changes and progression of the underlying operating systems

This means a longer term commitment to a product or service beyond its completion, including games, apps and other solutions.

• update

In its usage your solution might bring to light new demands, changed demand, missing features…. your design is not finished upon delivery.

When you look for example at apps on your smartphone, take note how many apps need regular updates (bug fixes being a notorious category).

Updating is something you need to take into consideration when writing your innovation plan. 99% chance it will come to light after initial deployment.

• upscale

Your solution might be so succesful it inspires others. It might spread to other organisations, other sectors, other user groups, other countries even… did you prepare for this possibility?

Upscaling means the scalability of your solution will now seriously be tested. Is it modular in design? Can language be changed? Hopefully, the right design decisions have been made to cater for this future.

These questions should have been asked and answered in the first step of the process!

But remember! Back to Front

Given all these steps for successful innovation, it is vital to discuss all these steps in the very first step of the process.

This includes asking nasty questions toi all stakeholders.

One example: many innovation trajectories will start with ‘a pilot’ or ‘a prototype’. Ask to all involved; where will the money be for the remainder of the trajectory (the blue and dark red tiles

The Awareness phase is often forgotten, following the ‘we will think about it when we get there’, the reason why a disturbing high percentage of innovation projects, apps, platforms and other solutions fail to reach the market and lead tot sustainable innovation.